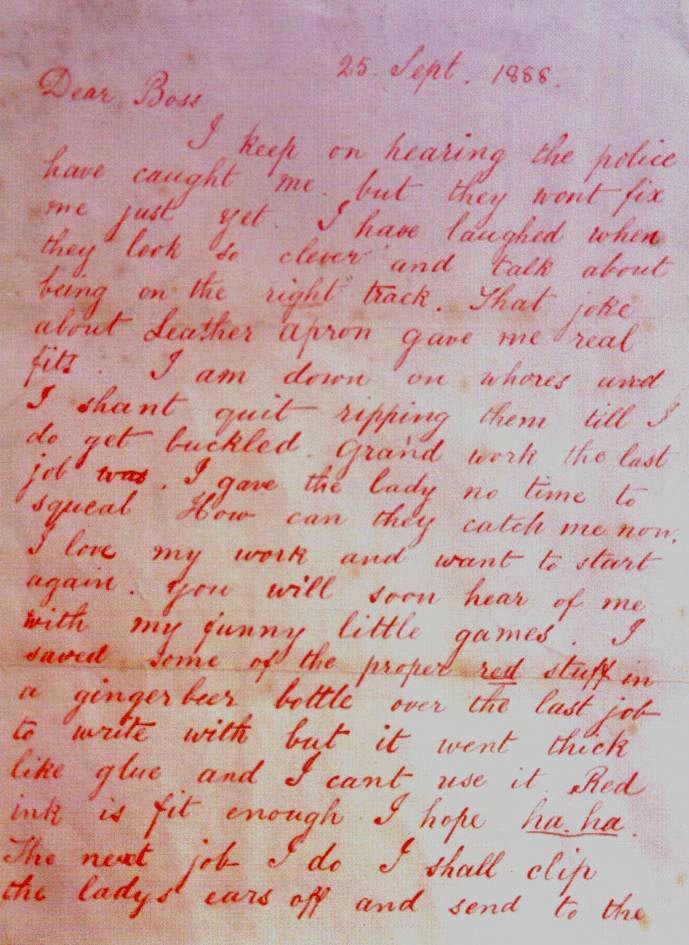

Red ink gleams darkly. The handwriting uneven and deliberate. “Dear Boss,” the letter begins, “I keep on hearing the police have caught me but they wont fix me just yet.”

With these chilling words, the world first encountered the name that would become synonymous with Victorian terror: Jack the Ripper. Yet behind this infamous correspondence exists a web of deception, journalistic manipulation, and questions that continue to haunt researchers more than a century later.

The Ripper letters are one of history’s most compelling cases of potential media fabrication, where the line between authentic evidence and calculated hoax blurs into shadow. These documents transformed a series of brutal murders into an everlasting cultural phenomenon.

The Birth of a Monster

The story begins on September 25, 1888, when the Central News Agency received a letter written in red ink, postmarked two days later. The timing is curious. This correspondence arrived after the murders of Mary Ann Nichols and Annie Chapman but before the double event that would claim Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes.

The letter’s author boasted of his “grand work” and promised more violence to come, signing with a name that would echo through history. Jack the Ripper.

What makes this document particularly sinister is its prophetic accuracy. The writer promised to “clip the ladys ears off and send to the police officers just for jolly”. When Catherine Eddowes was discovered murdered on September 30, investigators found her earlobe severed; a detail that seemed to validate the letter’s authenticity.

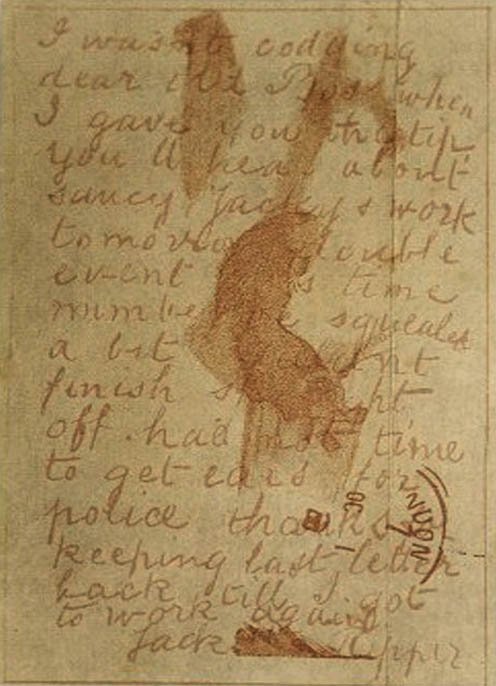

The “Saucy Jacky” postcard followed swiftly, arriving at the Central News Agency on October 1, written in similar handwriting and stained with what appeared to be blood. This postcard referenced the “double event” and boasted that the author had indeed attempted to collect ears for the police, exactly as promised in the earlier letter.

The timing appeared too perfect, perhaps.

The Web of Deception

Modern forensic linguistics casts a shadow of doubt over these iconic documents. In 2018, University of Manchester researcher Andrea Nini conducted a comprehensive analysis of 209 Ripper letters, applying sophisticated linguistic techniques to texts that had mystified investigators for over a century.

Nini’s research revealed striking linguistic similarities between the “Dear Boss” letter and the “Saucy Jacky” postcard, including distinctive phrases like “to keep back” instead of the more common “withhold”.

This linguistic fingerprinting strongly suggests both documents came from the same pen…but not necessarily the pen of a killer.

The analysis extends beyond these two famous letters. Nini discovered connections to a third document, the controversial “Moab and Midian” letter, also sent to the Central News Agency.

This pattern points to a troubling possibility: that these foundational Ripper documents originated not from Whitechapel’s blood-soaked streets, but from the desks of Victorian journalists.

The Media’s Dark Gambit

The Central News Agency stands at the centre in this sinister drama. This organization received not only the “Dear Boss” letter and “Saucy Jacky” postcard, but also the “Moab and Midian” letter.

A pattern too convenient to ignore?

Victorian newspapers thrived on sensational crime stories, and the Whitechapel murders provided perfect material for boosting circulation.

Evidence suggests that journalists may have crafted these letters to maintain public interest and increase newspaper sales. The practice wasn’t uncommon in Victorian journalism, where the line between reporting news and creating it often blurred.

The timing of the letters’ publication supports this theory; each appeared precisely when public attention might have waned.

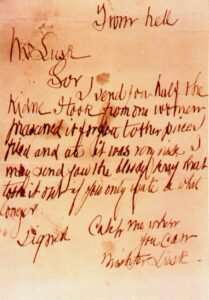

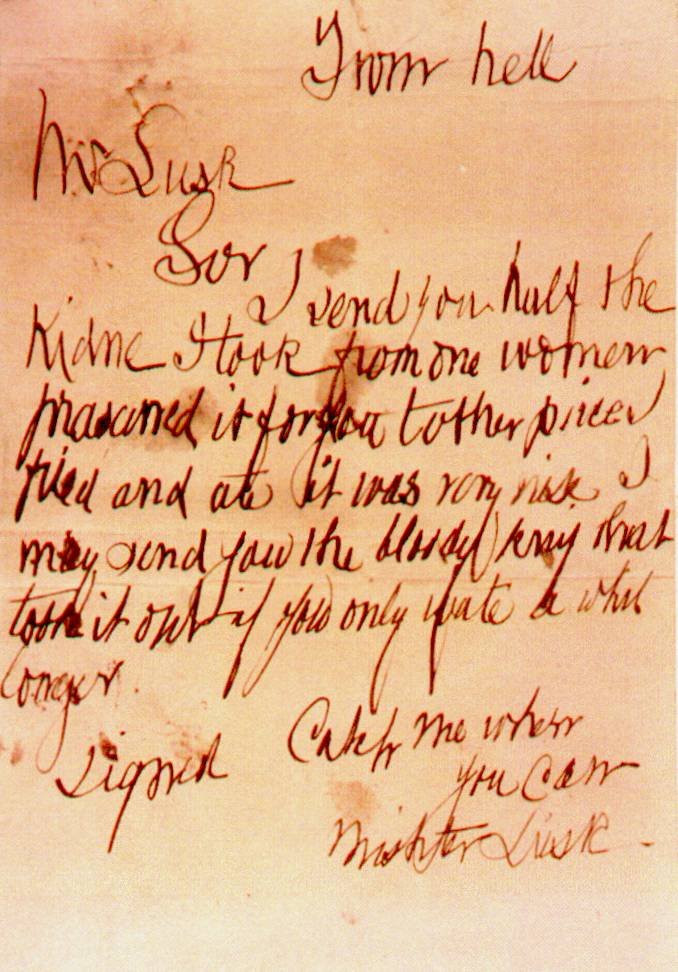

The “From Hell” letter stands apart from this pattern. Unlike the other correspondence, it arrived directly at the home of George Lusk, chairman of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, accompanied by half a human kidney.

The handwriting differs markedly from the “Dear Boss” and “Saucy Jacky” documents, and the author doesn’t use the “Jack the Ripper” signature. Some forensic experts consider this letter the only potentially authentic communication from the killer.

The Cascade of Fabrication

The publication of the initial Ripper letters triggered an avalanche of copycat correspondence. Hundreds of letters poured into police stations and newspaper offices, each claiming to be from the Whitechapel murderer.

This flood of false evidence created a nightmare for investigators, who had to examine each document while pursuing genuine leads in an active murder investigation.

The letters achieved something far more insidious than simple misdirection. They created a mythological persona around the killer. Before the “Dear Boss” letter, newspapers referred to the murderer by various names or simply as the Whitechapel killer.

The correspondence gave him a voice, a personality, and a name that transformed him from a flesh-and-blood criminal into a figure of legend.

The investigation suffered greatly from this transformation. Police resources became diverted into examining hundreds of hoax letters instead of focusing on physical evidence and witness testimony. The killer, meanwhile, operated in the shadows while his fictional persona dominated headlines.

The Anatomy of Victorian Sensationalism

The Ripper letters exploited Victorian society’s fascination with crime and mystery. The documents contained precisely the elements that would capture public imagination: taunting authorities, promising future violence, and reveling in gruesome details.

They read like something from a penny dreadful rather than genuine criminal correspondence.

The letters employ theatrical phrases and deliberately shocking imagery designed to provoke maximum reaction. The writer demonstrates awareness of public fascination with the case, referencing newspaper coverage and police theories.

This meta-textual quality suggests an author intimately familiar with media coverage rather than someone focused solely on committing murders.

Victorian journalism operated under different ethical standards than modern media. Newspapers competed fiercely for readers, and sensational crime stories guaranteed sales. The Ripper murders were a perfect storm of public fascination and media opportunity, creating conditions ripe for journalistic manipulation.

The Lasting Legacy of Deception

The impact of the Ripper letters extends far beyond their immediate effect on the 1888 investigation. These documents fundamentally shaped how society perceives serial killers, establishing tropes that persist in modern crime fiction and media coverage.

The image of a killer who taunts police and craves publicity can be traced directly to these Victorian fabrications.

Modern criminal profilers recognize that authentic serial killers rarely communicate with authorities or media. The compulsion to taunt investigators, so central to the Jack the Ripper legend, appears to be largely fictional.

The divide between myth and reality demonstrates the letters’ influence on public perception of criminal behavior.

The letters also established a template for hoax communications that continues today. Every major crime attracts fake confessions and fraudulent letters, echoing the pattern established during the Whitechapel murders. Investigators must still dedicate resources to examining these documents, just as their Victorian predecessors did.

Unraveling the Web of Truth

Recent technological advances have provided new tools for examining the Ripper correspondence. Forensic linguistics, handwriting analysis, and digital humanities techniques allow researchers to detect patterns invisible to Victorian investigators.

These methods consistently point toward journalistic rather than criminal origins for the most famous letters.

The evidence suggests a complex web of fabrication involving multiple parties. While the “Dear Boss” and “Saucy Jacky” documents likely originated from the same source (possibly a journalist), other letters came from different hands. The “From Hell” letter stands apart, bearing hallmarks that some experts consider authentic.

This patchwork of genuine and fabricated documents creates a puzzle that may never be fully solved. The passage of time has obscured crucial evidence, and many of the original participants took their secrets to the grave.

The Shadow of Doubt

The Ripper letters force us to confront uncomfortable truths about evidence, media, and public perception. These documents shaped one of history’s most famous criminal cases.

They demonstrate how fabricated evidence can become accepted fact, influencing not only contemporary investigations but also historical understanding.

The letters’ impact on the original investigation was devastating. Police chased phantom leads while the real killer continued his work. The flood of hoax correspondence buried any potentially genuine communications, creating noise that drowned out signal.

This pattern continues today, as hoax communications complicate modern criminal investigations.

Perhaps most troubling, the letters reveal how media manipulation can transform reality. The Jack the Ripper of popular imagination—the taunting, publicity-seeking killer—likely never existed. This figure emerged from the pages of Victorian newspapers, crafted by journalists who understood that fear sells papers and myth outlasts truth.

The Ripper letters are monuments to the power of deception and the dangers of accepting evidence at face value. They remind us that sometimes the most compelling stories are also the most fraudulent, and that truth often proves far stranger, and more disappointing, than fiction.

In the shadowy alleyways of Whitechapel, where five women died in terrible circumstances, the real killer worked in silence while his fictional counterpart dominated headlines around the world.

These documents continue to fascinate researchers and the public alike, not because they reveal the killer’s identity, but because they expose the complex relationship between crime, media, and myth. They serve as a cautionary tale about the seductive power of sensationalism and the lasting impact of well-crafted lies.

In the end, the Ripper letters may tell us more about Victorian journalism than Victorian crime. A legacy both fascinating and deeply troubling.

Discover more grusome and disturbing details about Jack the Ripper on our Jack the Ripper Walking Tour.